Taking the Geospatial Plunge (Part 1: Inspiration)

A sixth-century mosaic map on the floor of Saint George church in Madaba, Jordan. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

In the sixth-century city of Madaba , Jordan, a mosaic floor in Saint George’s church visually unites sacred space with the wider world—Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the Nile River, the Dead Sea are all represented in stone tesserae. The map suggests both devotion and action. Christian visitors who caught a glimpse of this twenty-foot wide mosaic could direct their prayers to God, and the church itself would direct the pilgrims to the Holy Land. Its scenes include cityscapes and houses, bodies of water with fish and boats, people at work. The mosaic was designed from a combination of bird’s eye views and non-linear perspective, letting the visitor’s visual experience shift between omniscient narrator and active participant. According to tradition, Moses gazed at the Promised Land from the top of nearby Mount Nemo. Art historian Antony Eastmond surmises that the Madaba map allowed pilgrims to reenact Moses’ experience by standing in the church and gazing down at the floor map’s image of the Holy Land spread out before them.[1] Maps like this tend to provide an intangible link between the viewer’s body and physical experience and the wider, imagined world, highlighting their participatory nature.

Bridging the gap between tangible, ancient cartographic arts and digital manifestations of them is Measuring and Mapping Space: Geographic Knowledge in Greco-Roman Antiquity, curated by Roberta Casagrande-Kim and Tom Elliott. This exhibition at ISAW (NYU’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World) explores the work of Greek and Roman geographers, known to us mostly through written sources and copies in medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. The show explores other objects, such as coins with depictions of places, and juxtaposes them with digital components, resulting in a thoughtful and multi-faceted exploration of human relationships and physical space.

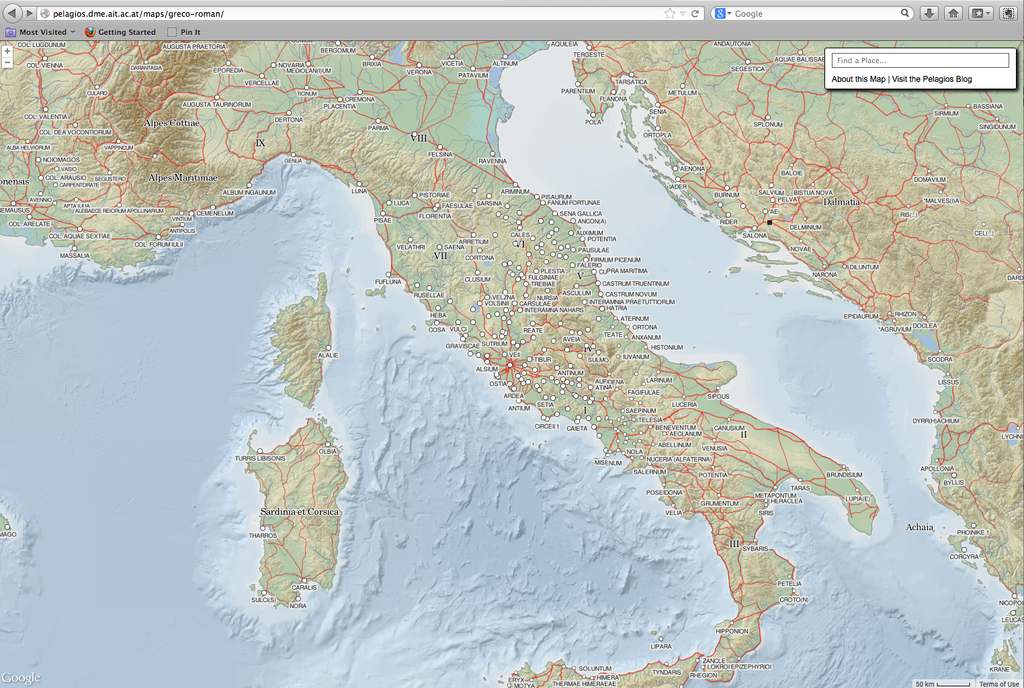

Fast forward a millennium or so, and one of my favorite online maps is Johan Åhlfeldt’s Digital Map of the Roman Empire on Pelagios. This is the map that made me love digital maps. It includes the Madaba sites and many more. There’s also Antiquity À-la-carte, an interactive GIS application of the Ancient World Mapping Center. In Antiquity À-la-carte, features such as settlements and churches are elegantly placed on a map of the medieval Mediterranean terrain, demonstrating at a glance how ancient communities were connected by roads and rivers. Zoomable, beautifully crafted with open data, and well-documented, this map represents the kind of project that drives both scholarship and public knowledge. I should note that both of these are part of the Pelagios network, a collaboration of around 30 ancient and medieval studies websites that rely on Linked Open Data.

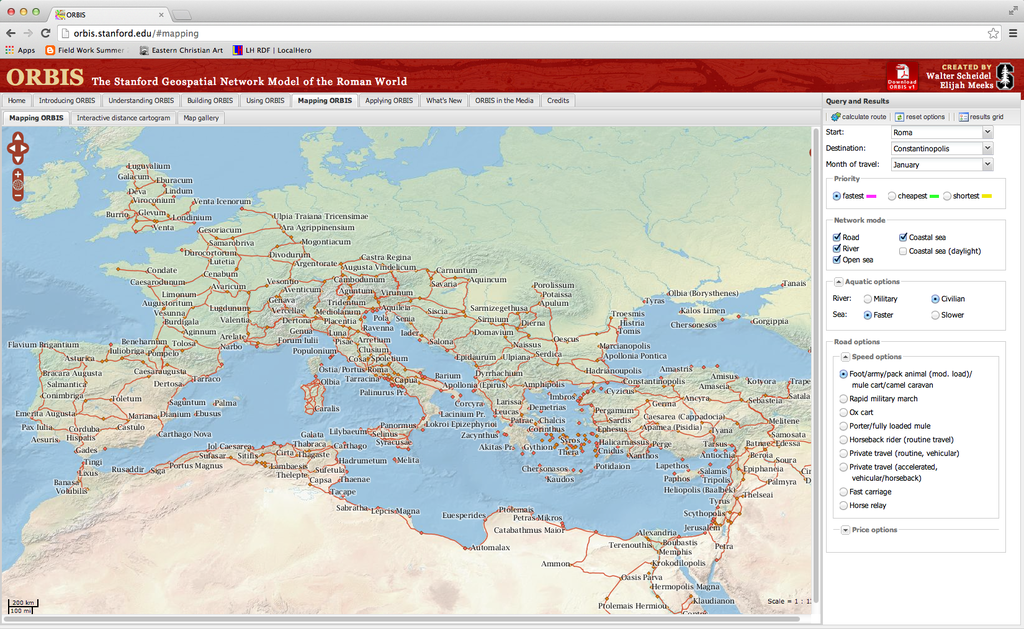

A similar project, ORBIS, goes beyond map representation to interactive tool. Essentially ORBIS is a travel planner for the ancient world that was created by Walter Scheidel and Elijah Meeks with a team at Stanford University. It goes beyond visualizing the ancient world, allowing users to determine variables and make calculations. I’ve used it in my own research to estimate how long it would take a monk to get from Caeserea, Cappadocia to Constantinople (15.8 days by horseback and sea in the month of June, in case you’re wondering). It’s also a good pedagogical tool, as evidenced by John Muccigrosso’s blog post on teaching archaeology.

These were the maps that hurled me into the digital cartography rabbit hole, making me want to understand how these projects actually work. In a juxtaposition of art and science, cartographic projects reflect the thoughtful decisions and interpretative nuances behind representations of geospatial data.

In future posts, I’ll consider issues and research questions as well as tools for making maps.

[1] Anthony Eastmond, The Glory of Byzantium and Early Christendom. (London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 2013), 108.