NYCDH Lightning Talk

“Reconstructing a Sacred Barrier: Testing the Virtual Waters of 3D Modeling”

The following is a lightning talk I gave on February 6, 2016 as part of the NYCDH Week Kickoff Gathering at Fordham University. It’s an update on my process and progress since beginning the project I detailed in the previous post.

I work on Byzantine rock-cut architecture in Cappadocia, a region in Turkey. Essentially my work is phenomenology, trying to decipher the lived experience in medieval monuments that are now abandoned, often badly damaged. At the heart of it, my work is about seeing—hopefully as the Byzantines did—using technology to “see” what is no longer there anymore, to notice details and re-imagine spaces that were once full of people and music and chanting and colorful clothing and flickering candlelight.

As you can see here (above), now most of them are full of dust.

My NYC-DH project will take my photos of a ninth-century chapel (with a tomb wall that was destroyed in the 1980s) and merge them with historical photos of the tomb wall intact. (See Jerphanion’s image, above).

This is still a work in progress.

The ultimate goal is to determine what viewers would have seen from a small window in the wall, from either side. This is part of a larger experiment wherein I model Cappadocian spaces using a variety of tools and techniques—photogrammetry, vector illustration or polygon mesh models, even pencil sketches and digital photographs—in order to capture the essence of a space.

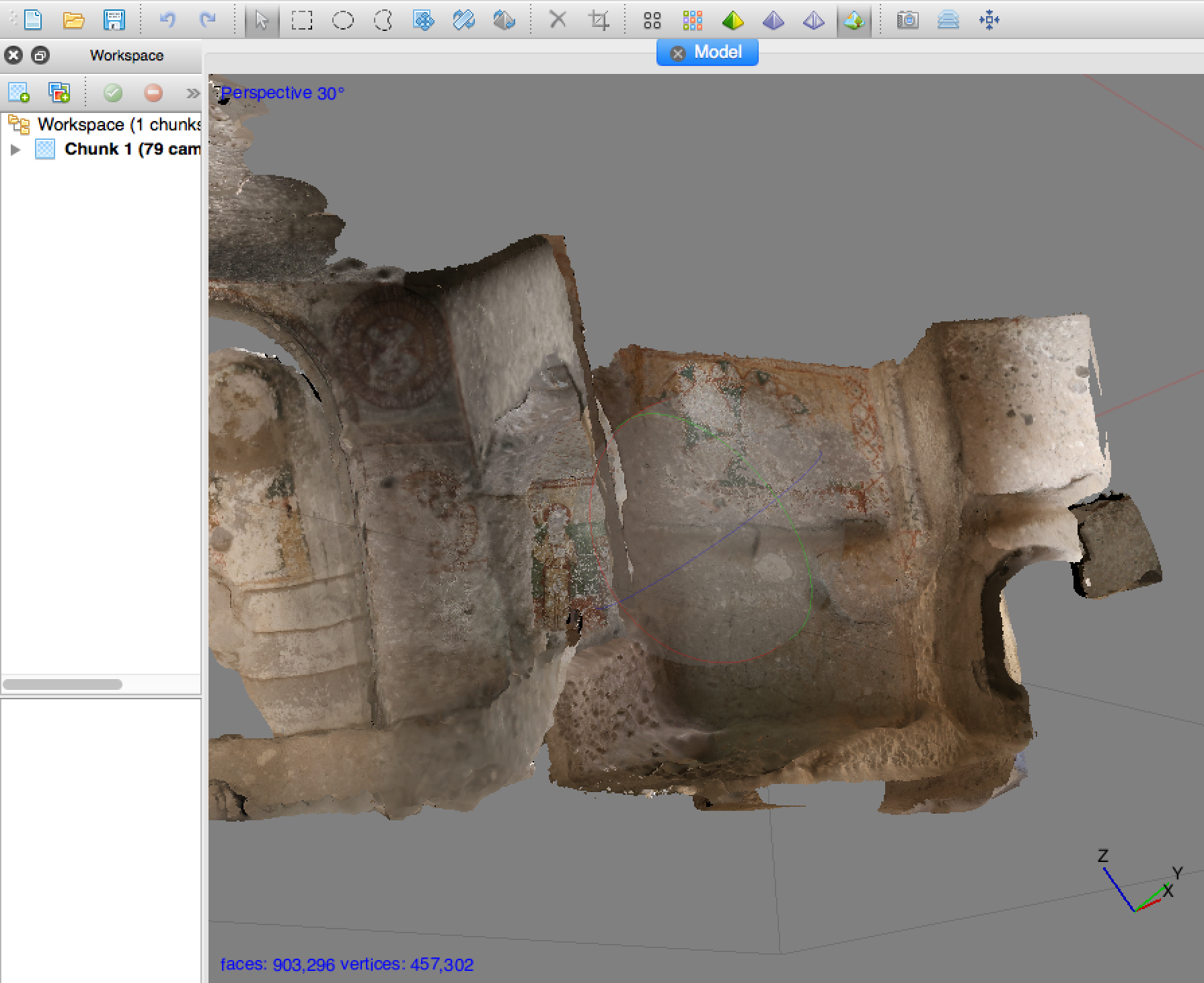

Screenshot of photogrammetry of the Karabas tomb; historical photos were not successfully integrated into the model.

This is a screenshot (above) of a first attempt at merging these two sets of photos using photogrammetry software to “stitch” them together and create an interactive model.

So far, my models aren’t pretty. But I’m here to argue that actually the process, the technique of creating a model is how we learn to see. The beauty, the quality of the replica is actually less important than what we learn from doing things that the space guides us to articulate or emphasize.

My original photogrammetry experiment didn’t work. That’s okay! I attempted to use historical photos within AgiSoft Photoscan, but the software couldn’t find a camera angle (because they’re just scans) so the older images did not register as useable data.

However, I was able to determine that the window was placed almost directly across from a niche on the opposite wall. This offers possibilities for interpretation already. And, I can use this model as background to trace the floor plan and create an architectural plan that is closer to actual scale. I can also use screenshots from the photogrammetry model when creating a vector illustration in SketchUp to achieve accurate proportions.

Sergius Test1 Feb2016

by Documenting Cappadocia

on Sketchfab

That is the next step: an illustrated model in SketchUp. The one above is a very simplified draft of a different chapel. So far it is lacking in detail and incomplete, but from it I learned a lot about how I estimated the proportions of the monument versus how they really measure up. I can start to look at the relationships between the ceiling decoration and other parts of the space.

The way we engage with ancient and medieval spaces is inevitably mediated by images of them, and by technology. We think of models as alternative or additive accessories to historical knowledge—even in our terminology: things like Virtual Reality, or Augmented Reality.

But there’s no one kind of representation that will replace lived experience. So by experiencing multiple types of modeling, and particularly by using them as interpretative rather than representative images, we see that they are also a way of breaking apart our preconceived notions about spaces and the past, revealing relationships between smaller elements and viewers.